The First Of The Protestant Reformation Martyrs

The monks of the convent of the Augustines at Antwerp who had received the truths of the Gospel

The convent of the Augustines at Antwerp was filled with monks who had received the truths of the Gospel. Several of the brethren who were domiciled in this monastery had dwelt for some time in Wittenberg, and, ever since the year 1519, salvation through grace had been preached in their church with much energy.

The prior, James Probst, an ardent person, and Melchior Mirisch, who distinguished himself by his talents and his prudence, were apprehended and taken to Brussels around the end of 1521. They there appeared before Aleander Clappio, and several other prelates. Surprised, alarmed, and interdicted, Probst retracted his opinions; but Melchior Mirisch knew how to calm the accusations of the judges, and at once escaped the penalty of condemnation and retraction.

These persecutions in no way terrified the monks left within the walls of the convent at Antwerp. They continued to proclaim the truths of the Gospel with energy, and the people hurried in crowds to listen to their preaching, insomuch that the church of the city was found too small to contain the eager multitude, in the same manner as the church at Wittenberg had before proved insufficient to accommodate the people there.

In October 1522 the storm which had been heard grumbling over their heads burst forth in all its fury. The convent was shut up, and the monks were thrown into prison and condemned to death. Several of them succeeded in making their escape, and a few women, forgetting the timidity of their sex, rescued one Henry Zuphten from the hands of the executioners. Three young monks, Henry Voes, John Esch and Lambert Thorn, concealed themselves for some time from the search of the Inquisitors. All the vases of the convent were sold; the building was strongly barricaded; the “holy sacrament” was taken away, as from an infamous place, and the governess of the Netherlands, Margaret, received it solemnly into the Church of the Holy Virgin. Orders were given not to leave one stone upon another belonging to this heretical monastery, whilst a number of citizens and some women, inhabitants of the town, who had listened with joy to the truths of the Gospel, were forcibly cast into prison.

Luther was overwhelmed with sorrow when he was informed of these harsh proceedings. “The cause which we defend,” said he, “is no longer a simple game; it looks for blood, it seeks for life.”

Mirisch and Probst were to follow very different courses. The prudent Mirisch became very soon the pliant servant of Rome and the executioner of imperious arrests against the partisans of the Reformation. Probst, on the contrary, having escaped from the hands of these inquisitors, repented of his error; retracted his recantation, and preached with boldness at Bruges, in Flanders, the doctrine which he had formerly abjured. Arrested a second time, and shut up in the prison of Brussels, his death appeared inevitable; but a Franciscan had pity upon him. and helped him to escape, so that Probst, “saved by a miracle of God,” said Luther, arrived at last in Wittenberg, where his double deliverance filled with Joy the hearts of the friends of the Reformation.

In every direction the Roman priests were under arms. The city of Miltenberg upon the Maine, which was attached to the provinces of the electoral-archbishop of Mentz, was one of the Germanic cities which had received the word of God with great eagerness. The inhabitants cherished a strong affection for the character of their pastor, John Draco, one of the most enlightened men of his age. He was obliged, however, to leave his home; but the Roman ecclesiastics, in alarm, went out at the same time from the city, dreading the vengeance of the people, and an evangelical deacon remained alone to afford consolation to the souls of the congregation.

At this moment some soldiers from Mentz rode into the town and took possession of it, their mouths filled with blasphemous words, and brandishing their swords. They also practiced every species of debauch in their conduct.

A few evangelical Christians fell under the blows of the intoxicated troopers; others were put into dungeons. The rites of Roman Catholicism were re-established, the reading of the Bible was interdicted, and the inhabitants were forbidden to speak of the Gospel even in their most familiar conversations with each other.

The deacon had managed to escape at the instant the soldiers entered into the house of a poor widow. He was informed against to the leader of the troop, who sent one of his men to take him prisoner. The humble deacon, hearing the voice of the soldier who sought his life, and finding that this man came in great haste, awaited his approach in a state of perfect peace. At the very instant, the door of the room was opened with much eagerness, the deacon walked forth at a quiet step to confront his enemy, accosted him with much cordiality and said – ‘I bid you welcome, my brother, here I am, plunge your sword into my bosom.” The fierce soldier, astonished, let his sword fall from his hand, and prevented afterwards any one from injuring the person of the pious evangelist.

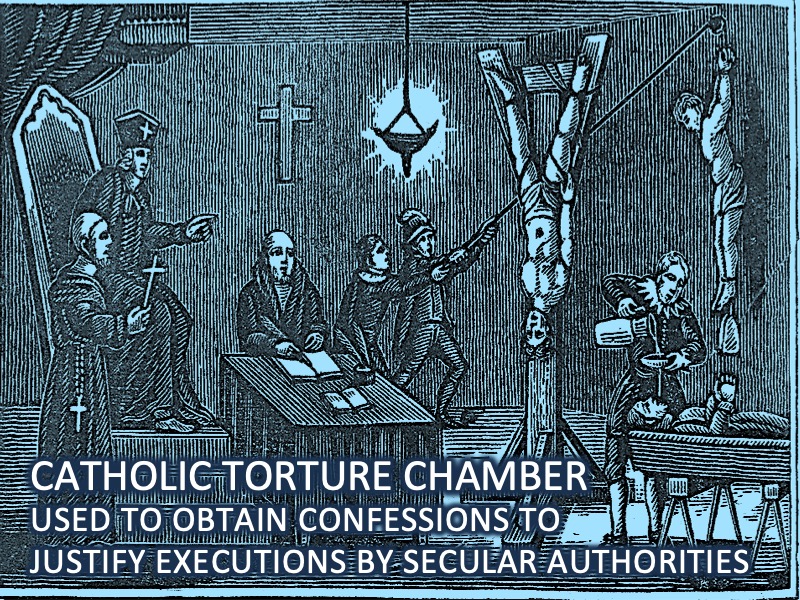

The inquisitors of the Netherlands, however, thirsting for blood, scoured the country, and sought out in every direction the young Augustines who had escaped from the attempts at persecution in Antwerp. Esch, Voes, and Lambert, were at last discovered, put in irons, and carried to Brussels, where Egmondanus Hochstratten, and some other inquisitors caused them to appear in their presence.

“Will you retract,” demanded Hochstratten, “your assertion that the priest has not the power to pardon sins, and that such a privilege belongs alone to God?” Then he enumerated all the other evangelical doctrines they were summoned to abjure. ‘No, we will not retract anything,” exclaimed Esch and Voes with constancy, ‘we will not deny the word of God, we will rather die for the truth of our faith.”

Inquisitor – “Confess that you have been seduced by Luther.”

The Young Augustines – “As the apostles were seduced by Jesus Christ.”

The Inquisitor – “We declare you to be heretics, deserving to be burned alive, and we hand you over into the hands of the secular power.”

Lambert remained silent, the fear of death beset him and agony and doubt agitated his soul. “I ask a respite of four days,” said he, in a stifled voice, and he was led back to prison. The moment the term of this delay had expired, the sacerdotal consecration was solemnly revoked with reference to Esch and Voes, and they were delivered over to the governess of the Netherlands. The council in turn gave them up, with their arms tied, to the care of the executioner. Hochstratten and the other three inquisitors accompanied the monks to the funeral pile.

When they arrived within a few steps of the scaffold, the young martyrs looked up to it with composure; their resolution, their piety, and their age, induced many present to shed tears; even the inquisitors. When they were bound to the stake the confessors approached – “We ask of you yet once more, are you willing to receive the Christian faith?”

The Martyrs – “We believe in the Christian church, but not in your church.” Half an hour was allowed to pass; hesitation was prevalent in the minds of the accusers; a hope was entertained that the prospect of a death so frightful would intimidate the hearts of these young men. But, alone tranquil in the center of the crowd, which in perturbation surrounded the scaffold they sang psalms, interrupting the tune at times by courageously repeating again and again, “We are willing to die for the name of Jesus Christ.”

“Become converted, become converted,” exclaimed the inquisitors, “or you shall die in the name of the devil.” “No,” replied the martyrs, “we will die like Christians, and for the truth of the Gospel.”

The fire was put to the funeral pile, and while the flames were seen to rise slowly towards the bodies of its victims a heavenly peace sustained their souls in so much that one of them was heard to say, “I feel as if extended on a bed of roses.” The solemn hour had come, and death hastily approached; the two martyrs meanwhile exclaiming with powerful voices, “O Domine Jesus, Fili de David, miserere nostril!” – Lord Jesus, the Son of David, have pity on us!

They then began to recite in a solemn tone the holy creed. At last the flames reached their bodies, but they consumed the cords with which the monks were bound to the stake before their breath was choked; and one of them, availing himself of this liberty, threw himself upon his knees into the midst of the fire, and thus worshipping his Master, he cried out, as he clasped his hands together – “Lord Jesus, the Son of David, have pity upon us!” The fire encompassed their bodies; they continued to sing aloud but very soon the smoke suppressed their voices, and they were reduced to nothing more than a heap of ashes.

This execution lasted four hours. It was upon the 1st of July 1523 that the first martyrs of the Reformation in this manner sacrificed their lives to the cause of the Gospel.

All men of worth trembled when they heard of this capital punishment, and they regarded the future with eager alarm. “The pains and torments have begun, ” said Erasmus. “At last,” exclaimed Luther, “Jesus Christ has gathered some fruit from our work, and he again creates happy martyrs.”

But the joy which the fidelity of these two young Christians occasioned Luther was interrupted by the thought of Lambert. This latter individual was the most learned of the three, and had replaced Probst at Antwerp in his office of preacher. Greatly grieved in his dungeon, and frightened at the prospect of death, Lambert was still more harassed by the accusations of his conscience on account of his dereliction, and its urgent warnings still to confess the Gospel. Speedily delivered from his fears, he boldly maintained the truth, and died a death similar to that of his brethren.

A rich harvest followed from the shedding of these martyrs’ blood. Brussels was turned in favor of the Gospel. “In every place where Aleander raises a funeral pile, ” said Erasmus, “it seems as if he sowed a quantity of heretics.”

“Your cords are my cords,” cried Luther, “your dungeons are my dungeons, and your funeral piles are my funeral piles!…We are all on your side, and the Lord is at our head.” He afterwards celebrated in a beautiful hymn the death of the young monks, and speedily, in Germany and the Netherlands, both in the towns and in the country, the words of these hymns were everywhere repeated, and seemed to spread abroad an empassioned enthusiasm for the faith of these martyrs –

“No! their ashes shall not perish,

In every place this holy dust,

Scattered to a distance, must

Bring brave soldiers God to cherish.

Satan truly snatched them from us,

And consigned them to the grave;

Still at their death he’ll madly rave,

When we sing aloud of Jesus.”