The Destruction of the Spanish Inquisition

Introduction

Founded in 1478, the Spanish Inquisition was not finally abolished until 1834.

In 1809 Colonel Lehmanowsky was attached to that part of Napoleon’s army which was stationed at Madrid. While in the city, the Colonel used to speak freely among the people what he thought of the Priests and Jesuits, and of the Inquisition. It had been decreed by Napoleon that the Inquisition and Monasteries should be suppressed, but the decree was not executed. Months had passed away, and the prisons of the Inquisition had not been opened. One night, about ten or eleven o’clock, as Col. Lehmanowsky was walking one of the streets of Madrid, two armed men sprang upon him from an alley. He instantly drew his sword, put himself in a posture of defense, and while struggling with them, he saw at a distance the light of the French patrols – mounted soldiers, who carried lanterns. He called to them in French, and, as they hastened to his assistance, the assailants took to their heels, and escaped, not, however, before he saw, by their dress, that they belonged to the guard of the Inquisition.

He went immediately to Marshall Soult, the Governor of Madrid, told him what had taken place, and reminded him of the decree to suppress the Inquisition. Marshall Soult replied that he might go and destroy it. The Colonel told him that his regiment (the 9th Polish Lancers) was not sufficient for such a service, but if he would give him two additional regiments, the 117th and another, he would undertake the work. The 117th Regiment was under the command of Col. De Lile, who, like Col. Lehmanowsky, became a minister of the Gospel and pastor of an Evangelical Church in Marseilles. The troops required were granted, and Col. Lehmanowsky proceeded to the Inquisition, which was situated about five miles from the city. It was surrounded with a wall of great strength, and defended by a company of soldiers. When he arrived at the walls, he addressed one of the sentinels, and summoned the holy fathers to surrender to the Imperial army, and open the gates of the Inquisition. The sentinel, who was standing on the wall, appeared to enter into conversation for a moment with someone within, at the close of which he presented his musket and shot one of Col. Lehmanowsky’s men. The Colonel then ordered his troops to fire upon those who appeared on the walls.

“It was soon obvious,” says Col. Lehmanowsky, “that it was an unequal warfare. The walls of the Inquisition were covered with the soldiers of the Holy Office. There was also a breastwork upon the wall, from behind which they discharged their muskets. Our troops were in the open plain and exposed to a destructive fire. We had no cannon, nor could we scale the walls, and the gates successfully resisted all attempts at forcing them. I could not retire and send for cannon to break through the walls without giving them time to lay a train for blowing us up. I saw that it was necessary to change the mode of attack, and directed some trees to be cut down and trimmed, to be used as battering rams. Two of these were taken up by detachments of men, as numerous as could work to advantage, and brought to bear upon the wall with all the power which they could exert, while the troops kept up a fire to protect them from the fire poured upon them from the walls. Presently they began to tremble, a breach was made, and the Imperial troops rushed into the Inquisition.

Here we met with an incident which nothing but Jesuitical effrontery is equal to. The Inquisitor-General and the Father Confessors, in their priestly robes, came out of their rooms, as we were making our way into the interior of the Inquisition, and with long faces, their arms crossed over their breasts, their fingers resting on their shoulders, as though they had been deaf to all the noise of the attack and defense and had just learned what was going on. The addressed themselves in the language of rebuke to their own soldiers, saying, ‘Why do you fight our friends, the French?’ Their intention, no doubt, was to make us think that this defense was wholly unauthorized by them, hoping, if they could make us believe that they were friendly, they should have a better opportunity, in the confusion of the moment, to escape. Their artifice did not succeed. I caused them to be placed under guard, and all the soldiers of the Inquisition to be secured as prisoners. We then proceeded to examine all the rooms of the stately edifice.

We passed through room after room: found all perfectly in order, richly furnished, with altars and crucifixes, and wax candles in abundance, but could discover no evidence of iniquity being practiced there-nothing of those peculiar features which we expected to find in an Inquisition. We found splendid paintings, and a rich and extensive library. Here was beauty and splendor, and the most perfect order on which my eyes had ever rested. The architecture, the proportions, were perfect. The floors of wood were scoured and highly polished. the marble floors were arranged with a strict regard to order. There was everything to please the eye and gratify a cultivated taste. Where, then, were those horrid instruments of torture of which we had been told, and where were those dungeons in which human beings were said to be buried alive? We searched in vain. The holy fathers assured us that they had been belied; that we had seen all; and I was prepared to give up the search, convinced the Inquisition was different from all others of which I had heard.

But Colonel De Lile was not so ready as myself to give up the search, and said to me: ‘Colonel, you are commander today, and as you say, so must it be; but, if you will be advised by me, let this marble floor be examined. Let water be brought and poured upon it, and we will watch and see if there is any place through which it passes more freely than others.’ I replied to him, ‘Do as you please, Colonel,’ and ordered water to be brought. The slabs were large and beautifully polished. When the water had been poured on the floor, much to the dissatisfaction of the Inquisitors, a careful examination was made of every seam in the floor, to see if the water passed through. Presently, Col. De Lile exclaimed that he had found it. By the side of one of these marble slabs the water passed through fast, as though there was an opening beneath. All hands were now at work for further discovery. Officers with their swords, and soldiers with their bayonets, sought to clear out the seam and pry up the slab; others, with the butt of their muskets, struck the slab with all their might to break it, while the Priests remonstrated against our desecrating the holy and beautiful house!

While thus engaged, a soldier struck a spring, and a marble slab flew up. Then the faces of the Inquisitors grew pale as did Belshazzar when the handwriting appeared on the wall. They trembled all over. Beneath the marble slab, now partly up, there was a staircase. I stepped to the altar and took one of the candles, four feet in length, which was burning, that I might explore the room below. As I was doing this, I was arrested by one of the Inquisitors, who laid his hand gently on my arm and with a very demure look said, ‘My son, you must not take those lights with your bloody hand; they are holy.’ ‘Well’ I said, ‘I will take a holy thing to shed light on iniquity; I will take the responsibility. I proceeded down the staircase. As we reached the foot of the stairs, we entered a large square room-The Hall of Judgment. In the center of it was a large block and a chain fastened to it. On this they had been accustomed to place the accused, chained to his seat. On one side of the room was an elevated seat-The Throne of Judgment. This the Inquisitor General occupied, and on either side were seats, less elevated, for the holy fathers when engaged in the solemn business of the Holy Inquisition. From this room we proceeded to the right, and obtained access to small cells, extending the entire length of the edifice. here saddening sights presented themselves.

These cells were places of solitary confinement, where the wretched objects of Inquisitorial hate were confined year after year, till death released them from their sufferings, and there their bodies remained until they were completely decayed, and their rooms had become fit for others to occupy. Flues or tubes, extending to the open air, carried off the effluvia. In these cells we found the remains of those who paid the debt of nature: some of them had been dead apparently but a short time, while of others nothing remained but their bones, still chained to the floor of the dungeon.

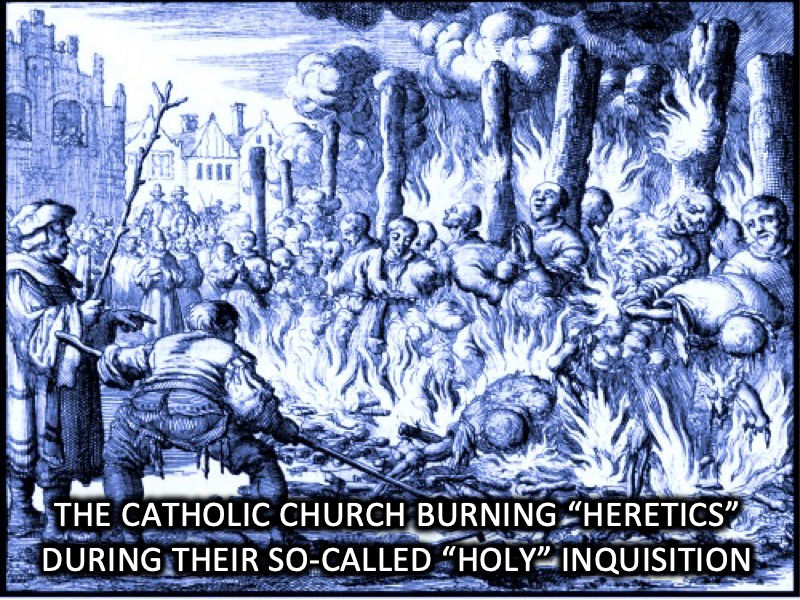

The Inquisition put their victims to the ‘question’ – they tortured them. If found guilty they were handed over to the secular authorities to be ‘relaxed’ – that is, burned to death.

In other cells we found living sufferers, of both sexes and of every age, from threescore years down to fourteen or fifteen years, all naked as when born into the world, and all in chains! Here were old men and aged women who had been shut up for many years. Here, too, were the middle aged and the young man and the maiden of fourteen years old!” The soldiers immediately went to work to release these captives from their chains, and took from their knapsacks their overcoats and other clothing, which they gave to cover their nakedness. They were exceedingly anxious to bring them out to the light of day; but Col. Lehmanowsky, aware of the danger, had food given to them, and then brought them gradually to the light, as they were able to bear it.

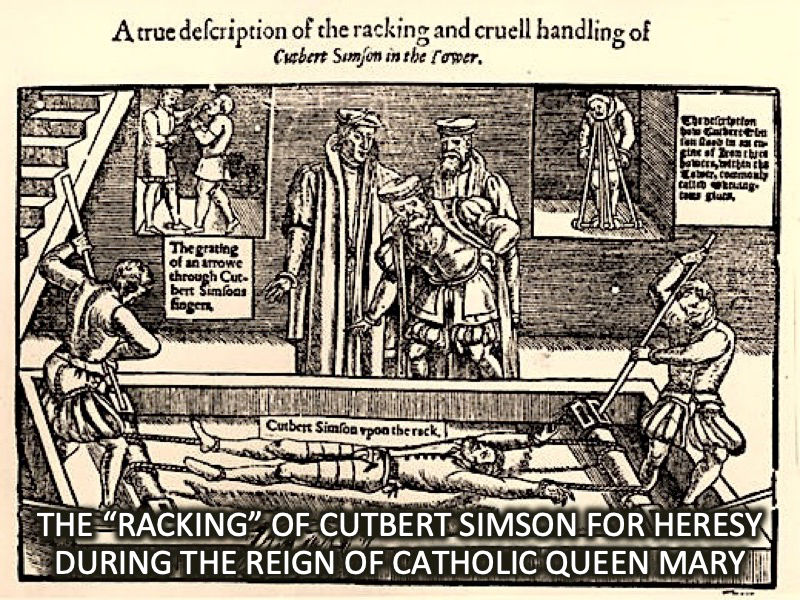

“We then proceeded to explore another room on the left. Here we found instruments of torture of every kind which the ingenuity of men or devils could invent.

The first was a machine by which the victim was confined, and then, beginning with the fingers, every joint in the hands, arms, and the body, was broken or drawn one after another, until the victim died.

The second was a box in which the head and neck of the victim were so closely confined by a screw, that he could not move in any way. Over the box was a vessel from which one drop of water a second fell upon the head of the victim. Every successive drop, falling on precisely the same place, soon suspended circulation, and put the sufferer in the most excruciating agony.

The third was an infernal machine, laid horizontally, to which the victim was bound. The machine was then placed between two beams, in which were scores of knives, so fixed that, by turning the machine with a crank, the flesh of the sufferer was torn from his limbs all in small pieces.

The fourth surpassed the others in fiendish ingenuity. Its exterior was a beautiful woman, or large doll, richly dressed, with arms extended, ready to embrace its victim. Around her feet a semicircle was drawn. The victim who passed over this fatal mark, touched a spring, which caused the diabolical engine to open; its arms clasped him, and a thousand knives cut him into as many pieces in the deadly embrace.”

Col. Lehmanowsky said that the sight of these infernal engines of cruelty kindled the rage of the soldiers to fury. They declared that every inquisitor and soldier of the Inquisition should be put to torture. Their rage was ungovernable. The Colonel did not oppose them. They might have turned their arms against him if he had attempted to arrest their work. They began with the holy fathers. The first they put to death in the machine for breaking joints. The torture of the inquisitor, put to death by the dropping of water on his head, was most excruciating. The poor man cried out in agony to be taken from the fatal machine. The Inquisitor-General was brought before the infernal engine called “The Virgin.” He begged to be excused. “No!” said they, “you have caused others to kiss her, and now you must do it.” They interlocked their bayonets so as to form large forks, and with these they pushed him over the deadly circle. The beautiful image instantly prepared for the embrace, clasped him in its arms, and he was cut into innumerable pieces. Col. Lehmanowsky said he witnessed the torture of four of them; his heart sickened at the awful scene, and he left the soldiers to wreak their awful revenge on the last guilty inmates of that prison-house of hell.

In the meantime it was reported through Madrid that the prisons of the Inquisition were broken open, and multitudes hastened to the fatal spot. And, oh, what a meeting was there-it was like a resurrection! About a hundred, who had been buried for many years, were now restored to life. There were fathers who had found their long-lost daughters, wives were restored to their husbands, sisters to their brothers, and parents to their children; and there was some who could recognize no friend among the multitude. The scene was such as no tongue can describe.

When the multitude had retired, the Colonel caused the library, paintings, furniture, etc., to be removed; and having sent to the city for a wagon load of powder, he deposited a large quantity in the vaults beneath the building, and placed a slow match in connection with it. All had withdrawn at a distance, and in a few moments there was a joyful sight to thousands. The walls and turrets of the massive structure rose majestically toward the heavens, impelled by the tremendous explosion, and fell back to the earth an immense heap of ruins–

THE INQUISITION WAS NO MORE!

— The Reformer – September/October 2001